Note: I plan to expand this section a little bit, but you could also just read the excellent lesson here: Chapter 2: Flow Control – for Loops and the range() Function

Why loop?

A loop is a programming construct in which we define a block of code that we want the computer to execute repeatedly, as well as how many times the computer should execute that block of code.

By "block of code", I mean, any code. For example, here's the Python code to print "hello world":

print("hello world")

And here's the script that repeats that "block of code" 5 times:

print("hello world")

print("hello world")

print("hello world")

print("hello world")

print("hello world")

That's simple enough. But what if I wanted to run that block of code 50 times. Or 5,000,000 times? Copy-and-paste can only get us so far.

But with a loop, we can command the computer to execute that block of code as many times as we want, without physically writing that code, over and over.

Here's what the previous print-hello-world-5-times script looks like, as a basic for-loop in Python:

for x in range(5):

print("hello world")

Anatomy of a very boring for-loop

Believe it or not, there's a lot to understand in that boring two-line snippet. Here are the highlights, which I'll elaborate on throughout this lesson.

- That range() function takes creates one of Python's data types. It's harder to accurately and completely explain than it is to just intuit: the range() function takes one argument and produces a sequence of numbers from

0up until that argument. The range() function itself is not a fundamental part of the _for-loop – I just use it in _this basic example as it's the easiest way in Python to say: hey, iterate 5 times. - However, what the

range()represents – a boundary condition – is fundamental to the for-loop: it specifies the number of times the loop should execute. - The keyword for is one of Python's few special keywords, i.e. you can't name a variable

for, and in a text-editor, it should be highlighted. - The keyword in is also another special reserved keyword.

- That

xis not a keyword. It's a variable name. And one that is superfluous since it's not actually used as anything right now but a placeholder. - That colon at the end of the for statement is required. It basically tells the Python interpreter: everything after this line is the block of code to be executed

- The block of code to be executed, e.g. that

print()statement, is indented 4 spaces. This is a requirement by Python, not just an aesthetic thing.

Execute a boring for-loop in interactive Python

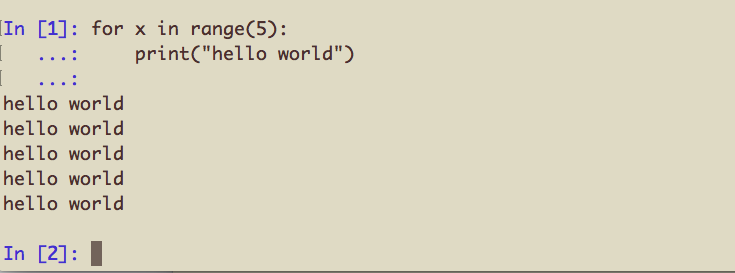

Before we get bogged down in the details, type out and execute the above code in the interactive Pythong interpreter (i.e. ipython). A few nuances will come up even in the execution of those two lines.

Note: if you are using ipython – which you should be doing – as soon as you hit Enter to go to the next line, the interpreter will automatically add an indentation for you. If you are using the regular python__interpreter, you will have to do this manually, either by hitting __Tab once, or the Spacebar 4 times.

Another note: When you type in the print("hello world") line and then hit Enter – nothing will happen. That is, the Python interpreter will prompt you for another line of code to execute as a block instead of printing out, "hello world". Just hit Enter one more time.

Here's what the code looks like when you type it out in ipython – note how ellipses are used to indicate the continuation of the code block inside the for-loop:

Variations on a very boring for-loop

So that's a very boring for-loop. Luckily, the construction of a for-loop doesn't get more complicated than what I've outlined above. However, it is critical that you understand the basic elements of a for-loop before moving on – i.e. the use of the keywords for and in, the colon at the end of the statement, and how the block of code to be executed is indented.

Before moving on, try these variations:

- Replace

xwithwhatever_variable_name_I_feel_like(or some other equally obnoxious but valid variable name) to confirm that the literalxcharacter is of no importance. - Replace the

5inside therange()function with5000or even5000000. Don't worry, this shouldn't break your computer. Though it may take a few minutes to finish. Hit Ctrl-C to break execution if you get bored. - Add a second line – e.g.

print("goodbye world")in the indented block of code.

Anatomy of a slightly less boring for-loop

Loops get a bit more exciting when you can create a task that varies upon each iteration. Remember that unused x variable in the first boring example? Let's include it in the print() statement to see what it contains:

for x in range(0, 5):

print("hello world", x)

The output:

hello world 0

hello world 1

hello world 2

hello world 3

hello world 4

Instead of printing just the same "hello world", over and over, we've managed to tell the computer to print something different with each iteration. Note that we haven't increased the complexity of the for statement at all. Though, to be honest, we haven't increased the complexity of the program's real world value by much either.

But let's have a brief segue and imagine how even just incrementing by one could be very useful in the real world. What if there were a collection of files or webpages that all were related or very similar, except for a single digit in the URL?

For example, Wikipedia has pages for a lot of things, including numerals. Here's the page for the number 1. Actually, it's the page for the year 1 A.D. – if you want the number 1, you want this URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1_(number)

OK, what if we wanted to print the URLs for the Wikipedia pages for the first 10 years (A.D.), starting with year 1 A.D.? The code and its output would look like this, if you try it at the interactive Python shell:

(note that the range() function can take a second argument, which creates a sequence of numbers from the first to the second argument)

(also note that we have to convert the number represented by the yr variable into a string literal in order to "add" it to the base URL)

>>> for yr in range(1, 11):

...: print("https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/" + str(yr))

...:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/3

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/4

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/5

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/6

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/7

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/8

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/9

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/10

What if you wanted the URLs for the Wikipedia pages that are about the numbers 1 through 10? Just modify the base URL a bit:

>>> for whatev in range(1, 11):

...: print("https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/" + str(whatev) + "_(number)")

...:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1_(number)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2_(number)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/3_(number)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/4_(number)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/5_(number)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/6_(number)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/7_(number)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/8_(number)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/9_(number)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/10_(number)

And what if we wanted to do something more interesting than just print out the URLs onto the screen? Such as download the pages? Or check to see if they exist? Or do this for another set of webpages?

Well, you can define that indented block of code to do whatever you want:

base_url = 'https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-and-releases?page='

for x in range(1, 11):

url = base_url + str(x)

print(url)

foo_bar_dosomethin(url)

Thinking and programming non-linearly with loops

Assuming you're reading this lesson before you've read the lesson on conditional branching, the for-loop statement will be the first time that you've explicitly written code that did not execute in the top-to-bottom order in which you wrote it.

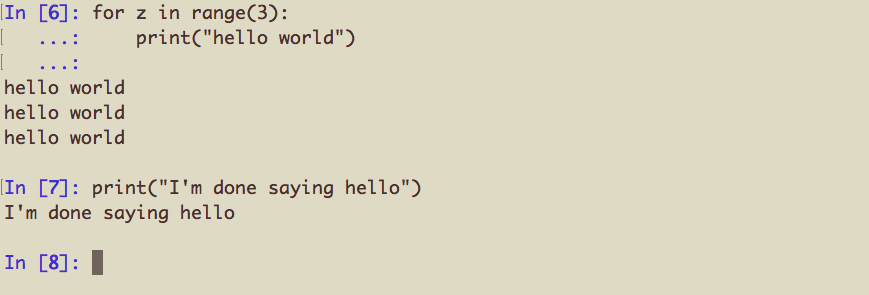

Consider this example:

for z in range(3):

print("hello world")

print("I'm done saying hello")

When I mean that the code executes non-linearly, I mean that even though this is the 3rd (and final) line of the script:

print("I'm done saying hello")

– it's not the third command to be executed. Instead, the 2nd line, the indented code block –

print("hello world")

– has to run its course. This is a much different paradigm than writing a script in which one line is executed after another.

In fact, to get the full effect of this lesson, implement the above snippet in two different ways:

1. Type it out in your interactive Python shell

Again, note how the indented code does not execute until you've hit Enter twice, consecutively, to signify the end of the indented code block.

2. Type it out and save as a standalone script

Now open up your text editor, write the code in a text file and save it. Then execute that file with the command-line Python interpreter:

$ python mytestscript.py

hello world

hello world

hello world

I'm done saying hello

How to interactively test a for-loop

One takeaway is that it can be a massive pain to write and execute even a basic for-loop inside the interactive Python shell, because the shell kind of stops being interactive when you indent a block, i.e. hitting Enter does not return a response.

So as you write more loops and other constructs that require indented blocks of code, I recommend that you just do it in the text editor with Python syntax highlighting, then paste it into the shell.

In fact, if you're using ipython (which, again, you should be using as your interactive shell), you can type in the special command %paste – which will paste in whatever is currently copied to your clipboard.

However, the proper way to test out a loop is to just run one iteration, and assign a value to the placeholder variable. Pretend that this is your complete script:

for xval in range(100):

url_part_a = "https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/"

url_part_b = "_(number)"

full_url = url_part_a + str(xval) + url_part_b

print("Downloading", full_url)

To test it interactively, simply assign xval as a normal variable. Then type out the rest of the indented block as if it existed as a standalone script, without that for-loop construct:

>>> xval = 42

>>> url_part_a = "https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/"

>>> url_part_b = "_(number)"

>>> full_url = url_part_a + str(xval) + url_part_b

>>> print("Downloading", full_url)

Downloading https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/42_(number)

One way to think if of this process is to pretend that you are inside the loop, and your only job is to execute the code block that occurs when xval is 42. You don't care that it's actually part of a loop, nor do you care that xval was previously 41, or that it will be 43. You just want to know what happens in one standalone execution of the indented code.

Because if it works for 42, or for any number between 1 and 100 – then you can be relatively assured that it will work for all those other numbers.

Sequences and other iterable objects

To keep things simple, I've used the range() function/object as the thing to be looped through, i.e. the sequence, i.e. the iterable.

There are many other sequences and iterable-type objects that can be used in a for-loop. I'll list the common ones below, but it is by no means an exhaustive list. For the most part, you learn what is iterable/loopable through experience:

Characters in a string

When a string literal is passed into the for statement, the code block will be executed for each character:

>>> for letter in "hello":

... print(letter.upper())

H

E

L

L

O

This is not actually something you see a lot in the wild. But it does work as a nice simple example a for-loop and iterable object…

A list or tuple

The list object is probably the most frequent iterable object you'll come across in Python:

numbers = [4, 5, 6]

for x in numbers:

print(x)

Tuples (which are basically simplified lists) work in a similar fashion:

numbers = (6, 7, 8)

for x in numbers:

print(x)

Reading a file, line by line

A file object in Python is a specific kind of iterable object, in which a stream of data is represented. When this is passed into the for-loop construct, the loop executes for every line in the file.

Pretend you have a file on your hard drive named example.txt, and its contents look like this:

hello world

and

goodbye

To open it, then loop through it line-by-line (with the code block simply printing out an upper-case version of each line):

>>> myfile = open("example.txt")

>>> for x in myfile:

... print(x.upper())

HELLO WORLD

AND

GOODBYE

Note: Why is there a blank line after each actual line of text? It's because in a text-file, each line of text has a newline character at the end of each line. And the print() function adds a newline character of its own…But explaining the nature of files requires its own guide…It's enough for now to see this as a real-life example of a for-loop.

Variations on loops

Understanding the for-loop construct is enough, as it is by far the most common kind of loop you will see in Python. However, it's worth pointing out the other variations and scenarios that you might see in the wild.

While loops

Just like for, the keyword while is reserved in Python. And similarly, while is also used to denote a block of code to be looped:

x = 0

while x < 3:

print("hello world", x)

x += 1

With the for-loop, you specify a collection of items to be iterated across. With a while-loop, you specify a condition that, if True, means that the code block should be executed. In the above snippet, the variable x is incremented with each iteration of the loop. When x represents the value 3, the condition becomes False, and the loop stops.

Think about what the equivalent for-loop would look like, then try to write it down. Here's my answer (note that there are literally infinite number of ways to represent this loop, because math and etc.):

for z in range(0, 3):

print("hello world", z)

Infinite loops

What if a condition is always True? Then, that loop will run forever, theoretically, as long as the laws of logic don't change. Practically speaking, of course, it will probably end when your computer runs out of power or the universe reaches heat-death.

Here's an example of an infinite while loop:

while 2 > 1:

print("hello world")

Or to be more succinct:

while True:

print("hello world")

And sometimes, you might accidentally write a loop that you don't realize will be infinite:

x = 0

while x < 3:

print("hello world", x)

x + 1

Since the value represented by x never changes (i.e. x is never reassigned the result of x + 1), the value of x is forever at 0, i.e. less than 3.

Non-looping loops

What if a while loop condition is always False? Then the code inside the loop will never run:

while 2 < 1:

print("hello world")

while False:

print("hello world")

It's pretty easy to create a for-loop version of the non-executing loop:

for x in range(0):

print("hello world")

for x in [ ]:

print("hello world")

While there are real-world reasons to have infinitely-running loops – usually you don't intend to write a loop that never actually loops.

Loops within loops

A code block within a loop is just like any other code you might write. It can be multi-line, for example. Or it could include other code blocks, including another separate loop:

for x in range(10):

for y in range(5):

for z in range(3):

print(x, y, z)

Can you guess how many lines of output the above script (which is as pointless as it seems)? Don't worry, in real-world scripts, loops-within-loops will usually make more sense, e.g. it won't involve just going through a range of arbitrary numbers. However, loops-inside-of-loops can get confusing very quickly. If your program is as confusing as triple-Inception, there is most likely a more elegant way to tackle the problem.

Teasers and exercises

The following exercises involve examining relatively simple for-loops. The purpose is to make sure you can confidently recognize what a for-loop looks like, even if the code block to be executed seems pointless or pointlessly complicated.

Fix these scripts

These simple for-loop examples all contain syntax errors. See if you can spot them:

for x in range(5):

print("hello world")

for number_in range(5):

print("hello world")

for really_big_number in really_embiggened_range_of_nuumbers

print("hello world")

Try to predict the output of these scripts

This is more of a test to see if you understand variable assignment

a = "whatever"

for x in range(42):

a = x

print(a)

You can do anything in a loop. Even math:

a = 0

for x in range(3):

a = a + x * 10

print(a)

What happens if we've defined a loop to run exactly 0 times:

a = 100

for number in range(0):

a = a + number

print(a)

This is actually just another test of understanding variable assignment:

a = 100

b = 200

for number in range(3):

b - a - number

for number in range(100):

a + b * number

print(a)

print(b)

Just in case you're confused by the syntax – or more likely, the real-world purpose of the script above – first of all, programming doesn't need to have a "real-world" purpose, as far as the interpreter is concerned. As long as the syntax is fine, the computer will run the program, no matter how meaningless it is to the real world.

Second, what you are meant to recognize is that whether it's in a single for-loop or a loop-inside-a-loop – the statement, a + b does just exactly that: it adds the contents of a and b together. That there is no effect at the end is a consequence of no variable assignment being done: i.e. the values of a and b are never reassigned. Hence, the boring output at the end.

For the purposes of this curriculum, I will never have you intentionally write a program this pointless. But that's not the point – you may accidentally write a pointless program. Not being able to see the logic error inside the for-loop is sometimes a result of not being comfortable with the for-loop syntax in the first place.

Were those exercises too simple? I've deliberately made them easy. It's only important that you understand and recognize the syntax of a for-loop statement. That's not meant to be the complicated part. But when you write complicated programs that involve for-loops, you do not want the basic syntax and operation of a for-loop to be a source of confusion for you.

Moving on

Read the lesson on conditional-branching (i.e. if/elif/else statements).

Then see if you can complete the infamous FizzBuzz test.