Quick cheat sheet

A quick guide to common downloading tasks.

Downloading a file

import requests

resp = requests.get("http://www.example.com")

## Reading as text

resp.text

## Read as bytes

resp.content

Downloading a URL with parameters

To fetch a URL contains a query string, e.g.:

http://www.example.com?name=Daniel&id=123456

The query string is: ?name=Daniel&id=123456

We can pass a dict into the params argument of the get() method. It will serialize the dict as the query string:

import requests

resp = requests.get("http://www.example.com",

params = {"name":"Daniel", "id": 123456})

print(resp.url)

# http://www.example.com/?id=123456&name=Daniel

About the Requests library

Our primary library for downloading data and files from the Web will be Requests, dubbed "HTTP for Humans".

To bring in the Requests library into your current Python script, use the import statement:

import requests

You have to do this at the beginning of every script for which you want to use the Requests library.

Note: If you get an error, i.e. ImportError, it means you don't have the requests library installed. Email me if you're having that issue, because it likely means you probably don't have Anaconda installed properly.

The get method

The get method of the requests module is the one we will use most frequently – which corresponds to how the majority of the HTTP requests your browser makes involve the GET method. Even without knowing much about HTTP, the concept of GET is about as simple as its name: it will get a resource from a web server.

The get() method requires one argument: a web URL, e.g. http://www.example.com. The URL's scheme – i.e. "http://" – is required, even though you probably never type it out in your browser.

Run this from the interactive prompt:

>>> requests.get("http://www.example.com")

<Response [200]>

You might have expected the command to just dump the text contents of http://www.example.com to the screen. But it turns out there's a lot more to getting a webpage than just getting what you see rendered in your browser.

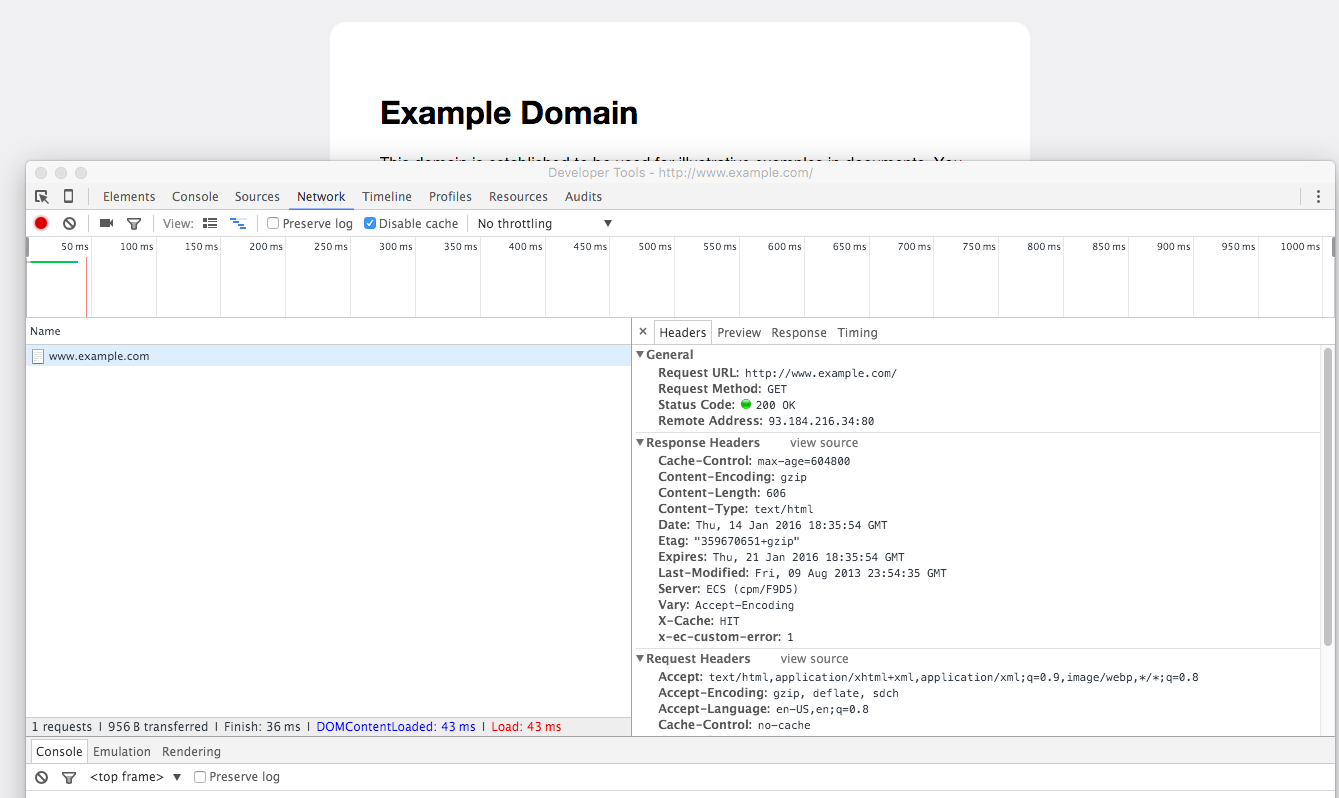

You can see this for yourself by popping open the Developer Tools (in Chrome, for OSX, the shortcut is: Command-Alt-J), clicking the Network panel, then visiting a page:

What each of those various attributes mean isn't important to figure out now, it's just enough to know that they exist as part of every request for a web resource, whether it's a webpage, image file, data file, etc.

Returning to our previous code snippet, let's assign the result of the requests.get() command to a variable, then inspect that variable. I like using resp for the variable name – short for "response"

>>> resp = requests.get("http://www.example.com")

Use the type() function to see what that resp object actually is:

>>> type(resp)

requests.models.Response

If you want to get the text of a successful requests.get() response, use its text attribute:

>>> resp = requests.get("http://www.example.com")

>>> print(resp.text)

The output will look like this:

<!doctype html>

<html>

<head>

<title>Example Domain</title>

<meta charset="utf-8" />

<meta http-equiv="Content-type" content="text/html; charset=utf-8" />

<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1" />

<style type="text/css">

# .... and so on